What is the highest good? What is that which all acts ought to aspire towards and be subservient to? Adam freshly formed from the dust of Eden, the first ray of light, took to naming every living creature as his first act, an act of illumination. The philosophers will give us happiness or well-being (eudaimonia) as the highest aim of moral thought and conduct, and the virtues (aretê: ‘excellence’) as the dispositions/skills needed to attain it. We will take it as apparent that beauty has the greatest effect on a person's happiness and well-being. Thus, it will be taken as the highest good, eudaimonia being dependent upon it, and the virtues needed to attain it being discernment and what has been termed “purity of disposition.” Transposing utilitarianism's definition of “the morally right action is the action which produces the most good,” we arrive at aesthetic utilitarianism: the morally right action is that which produces the most beauty, achieved by a purity of disposition and sound discernment.

The word perfection comes from the Latin word perficere, perfuctum (per-factum), perfect, and signifies that which is completely made. To perfect something is to liberate it unto the entirety of its essence. Perfection of the self, liberation of the self, is a precursor to both just discernment and purity of disposition. Now we must inquire what it means to perfect yourself, to become a liberated man, and the role of liberation in the pursuit of beauty. To do this we will contemplate the greatest act of discernment in Western civilization, the fountainhead of art and culture, Apollo and Dionysos.

Apollo was the God of both poetry and medicine, a curious connection. Friedrich Schiller, John Keats, Gottfried Benn, and William Carlos Williams were all practicing doctors, among other notable poets. Apollo is the god of both poetry and of medicine because the perfection of oneself comes from both the perfection of the soul (poetry) and the perfection of the body (medicine). To know oneself—as inscribed above the oracle at Delphi, Γνῶθι σεαυτόν— is to perfect oneself, to liberate oneself. This is the meaning of Heraclitus’ Ethos Anthropos Daimon (“character is fate”). Art is the passage of the soul into higher forms. The artist himself is liberated, set free into the entirety of his essence—man is made immortal by beauty. The greatest techniques towards this are of course prayer and study, or more precisely, contemplation as such. Thus, we arrive: to become a liberated man is to perfect oneself, and to perfect yourself is to know yourself transcendentally. To know yourself is an act of discernment, to perceive the nature of your innermost being, to judge what is rightly yours, and doff the chaff. It is the realization of your metaphysical necessity—to become yourself is to actualize the entirety of your metaphysical potential, and most people do not achieve this in their lifetime. Knowing yourself and discernment enjoy a recursive relationship, as do knowing yourself and purity of disposition, wherein better knowing yourself provides better powers of discernment, and better powers of discernment allow you to better know yourself, and so on.

Discernment, then, is that which creates space for the good to perfect the nature of a thing. Judgement, justice, perception, discretion, discrimination—taste, in short. Taste creates space. Discernment is the ordering of phenomenological reality by means of taste, and taste is both bred and cultivated. To perceive an object is already an act of discernment, as prior to the perception was an unconscious ordering of phenomenological reality into a hierarchy of importance, placing the perceived object at the top. This structuring of reality, separating each thing into its elements, is what creates space. This space allows for the juxtaposition of multiple elements, which allows for their further analysis and appreciation via ‘negative’ means as it is precisely their difference which reveals their essence, as hot is hot by virtue of being opposite of cold, and vice versa.

This bipodal tension is what creates the energy of animation—it is fire, “a spark from the old flint,” the gift of Prometheus. But fire is not only virility, it is also pure destruction. Prometheus was chained to a cliff to die for eternity. This is a violent matter full of violent deaths. There is no beauty without death; that delicious word death, lisp’d to Whitman by the wine-drunk sea. These are beautiful deaths; the world composting itself for the gaiety of flowers. You must be a pillar of man: man holding up man in a great ladder of atlas unto the heavens. Firm, concrete, and sturdy. No sway in the winds of time—an affront to the throes of Jove—you must pierce yourselves from heaven to hell—a poetics of the javelin—thrown by man to heavens and returning downwards to death, cleanly tearing through all which it comes in contact with.

The restructuring and synthesis of these elements is the particular domain of the imaginative faculty, and it is with taste which one selects his elements. The space created by taste is palpable: the open air Whitman and Nietzsche is precisely this. It is the wild frontier, the open road, the intrepid sea: it is the west. Leisure too is this space, though our understanding of it has been corrupted post-industrial-revolution.

The Romans referred to Dionysos as Liber Pater (“the free Father”). Melville said “the harpooners of this world must start to their feet out of idleness, and not from out of toil,” and what is the harpooner but the poet at the prow, ready to pierce the heart of leviathan, and drag him back for the philosophers to dissect on deck? “I loaf and invite my soul,” says Whitman, and the ancient British bards held for the title of their order: “Those who are free throughout the world.” Cicero held as his motto Otium cum Dignitate (“Leisure with Dignity”). Samuel Johnson spent his life defending idleness, and authored a periodical entitled The Idler. To be an idler, to loaf and invite one's soul, is the freedom to leisure, an act of non-production, opposed to its colloquial usage in the post-industrial world meaning laziness, or sloth. It is from the freemen alone, the loafers, that culture springs. Leisure, or scholē for the Greeks, is the foundation of the liberal arts (liber meaning free; i.e. one must be a free man before studying the arts, an opinion long held through the high middle ages) and the liberal arts are the foundation of Western Civilization. The liberal arts were the arts that the Romans taught to free men. Slaves might be taught to be ship captains or architects or doctors and in that way you could have a much more profitable slave, but no one taught a slave literature because it improves you as a person, not as a means of profit. Liberal arts are the arts worth teaching a person who has no need to be profitable, only a need to flourish. Analogous to discernment creating space for the perfection of an object, liberating oneself via gnosis (‘know’ in the Delphic maxim “know thyself” is meant in the sense of gnosis: an immanent form of knowledge or transcendent insight) creates the internal space for leisure, and thus the production of culture. The liberated man is he who engages art not as a means but as an end, i.e. beauty for beauty’s sake, l'art pour l'art.

There is one thing in the universe whose essence is independent, i.e. not a constituent element of another thing, and is usually recognized as the Christian God. This is also the source of his imperceptibility; if objects are perceived by their relation to another, and deity exists independently, then we are left with either an approach by humble silence (mysticism), or by constantly juxtaposing with force (revelation). This is the metaphorical realm, the language of the Bible and of poetry. The imaginative faculty’s restructuring of elements wherein their truths more distant and obscure are revealed by juxtaposition is precisely what is referred to as metaphorics. A corollary worth exploration, though it won’t be undertaken here, is that this deconstruction and restructuring of elements is not only a precursor to metaphorics, but to logic as well, most notably the syllogism. The syllogism is the direct logical counter to the metaphor. Even this distinction between the logical (a=b, b=c, a=c) and the metaphorical (a=/=b) is but another bipodal system resulting from discernment.

We may then glimpse a vision of the ideal aesthete as the cross by way of synthesis in the imaginative faculty. Let us view the Apollonian as the vertical "static" bar, and the Dionysian as the horizontal "dynamic" bar, and the purified aesthete, the poet-artist, is crucified upon this cross. He must through his head and feet be planted to the static transcendent principles, but the laws of the universe demand that the manifestation of those principles be contained within horizontal dynamic movement.

Disposition is a sub-function of the will and its purification is the aesthetic perfection of the will imposing itself on the world as form. Milton says, that the lyric poet may drink wine and live generously, but the epic poet, he who shall sing of the gods, and their descent unto men, must drink water out of a wooden bowl. Fine art is impossible without men of pure disposition. The great flourishes of humanity throughout history were precisely those civilizations of pure disposition, Sparta being the most dispositionally pure civilization in recorded history, and Christ’s martyrdom the most dispositionally pure phenomena. Purity of disposition instantiates itself on smaller scales as well, an amusing example being The Peregrine by J. A. Baker. Chess is an exceptionally pure vocation. Japanese cuisine and architecture. Science in its highest expression as well, being a sub-domain of discernment.

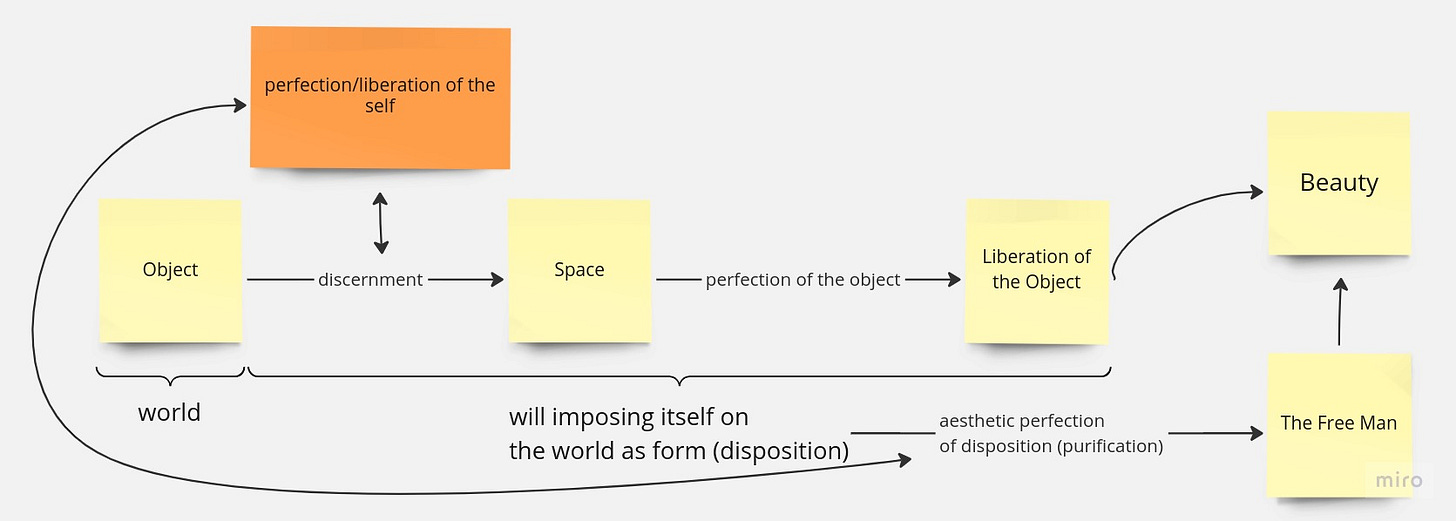

Therefore, we may conclude that the highest good is beauty, and it is attainable through the perfection of oneself, through discernment, and through purity of disposition. That which all acts ought to aspire towards and be subservient to, is beauty. We can now diagram the structure as such:

Beauty is then revealed to be a product of the liberated man setting an object free into the entirety of its essence; hence Adam, the first poet in his naming of every thing. “When lyric poetry becomes spiritualized and reaches the sublime it ends in mere enumerations, in uttering dear names with a sigh [...] There is no deeper love-sigh than the repetition of the beloved name, relishing it like honey in your mouth.” One must conclude that man felt the need of talking even when he was alone, that is to say, talking to himself, which is the same as singing, so that his act of naming the creatures was an act of lyrical purity. He invented the names to enjoy them in ecstasy. To tear man from his beastly coil and thrust him heavenwards, to enslave all else to that end, is the doctrine of aesthetic utilitarianism. The end of art is the return to paradise.

The poetic, that is, the beautiful, takes on a myriad of forms, quo Emerson from The Poet:

I will not now consider how much this makes the charm of algebra and the mathematics, which also have their tropes, but it is felt in every definition; as, when Aristotle defines space to be an immovable vessel, in which things are contained; -- or, when Plato defines a line to be a flowing point; or, figure to be a bound of solid; and many the like. What a joyful sense of freedom we have, when Vitruvius announces the old opinion of artists, that no architect can build any house well, who does not know something of anatomy. When Socrates, in Charmides, tells us that the soul is cured of its maladies by certain incantations, and that these incantations are beautiful reasons, from which temperance is generated in souls; when Plato calls the world an animal; and Timaeus affirms that the plants also are animals; or affirms a man to be a heavenly tree, growing with his root, which is his head, upward [...] when Orpheus speaks of hoariness as "that white flower which marks extreme old age;" when Proclus calls the universe the statue of the intellect; when Chaucer, in his praise of 'Gentilesse,' compares good blood in mean condition to fire, which, though carried to the darkest house betwixt this and the mount of Caucasus, will yet hold its natural office, and burn as bright as if twenty thousand men did it behold; when John saw, in the apocalypse, the ruin of the world through evil, and the stars fall from heaven, as the figtree casteth her untimely fruit; when Aesop reports the whole catalogue of common daily relations through the masquerade of birds and beasts; -- we take the cheerful hint of the immortality of our essence, and its versatile habit and escapes, as when the gypsies say, "it is in vain to hang them, they cannot die.”

If we take the deed, the phenomena in itself, we find beauty in equal proportion. In Melville raging across the intrepid sea, and Rimbaud running guns in Africa. Bold brawny Muir in his young Wisconsin farm reading Milton by candlelight in hours stole from the night, and big bearded Whitman yawping and yawning with the free-range ridin’ cowpokes. The blindness of Homer and of Milton, too. Fantastic conquerors of the globe. The deaths of Shelley and Hart Crane. There is no act more noble than devoting ones self, ones life, to this production. Beauty is not a property, it is objective, a physical quantity, to be cultivated as the wheat berry thrust into the earth, in the hopes it will bloom under proper care. One may even speak of a ‘bushel of beauty’ with no need for poetic licence. There are transcendent deeds, acts of single men which affected divinity; the noblest and most beautiful act being martyrdom, and Christ the greatest poet. There is nothing without sacrifice. He who lives and acts must suffer.

So we take ourselves new Epicureans: gluttonous beasts of prey engorging ourselves on everything in sight. Chasing down a portly passage of Goethe with another more wild of Whitman, Turner for an appetizer, maniacally drunk on pleasure, but digesting at exactly the rate proper, savoring every drop of every thing, and shitting out the waste. A race of Adams and this world our paradise! We who know no season, we for whom the world is an eternally bountiful banquet in wait of our tasting, we who know no greater pleasure than that of Adam: to stroll through the gardens of life plucking its ripe fruit, singing to ourselves and to God.